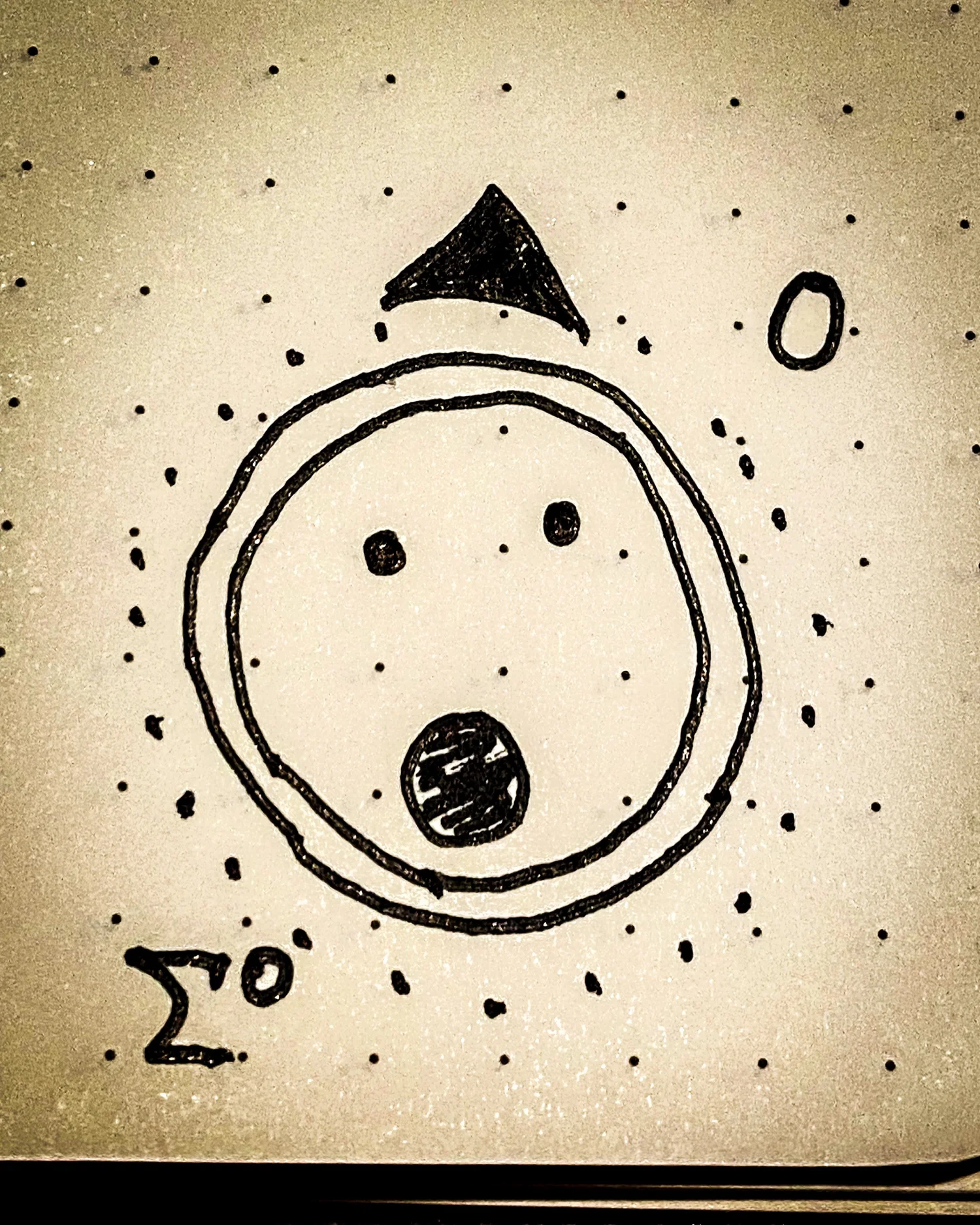

The Neutral Sigma Baryons

Weighing in at 1192 MeV, the middle-weight Σ baryon is also the the electrically neutral one.The Σ Baryons are a trio of strange, slightly heavy cousins to everyday particles like the proton and the neutron. We’ve already talked at length about the charged Σ baryons. Today, we’re focusing on their electrically neutral sibling, Σ0.

While the decay resistant charged Σ baryons - with their unusually long lifetimes - certainly qualify as “strange” particles, the Σ0 feels far less strange. At least at first.

The Σ0 decays rapidly. Tens of trillions of times faster than its charged siblings Σ+ or Σ-. If you’re into really small numbers, or just to measure time in seconds, that’s a decimal point followed by 19 zeroes before you get 7 and then a four.

0.000000000000000000074 seconds

That’s too short a time for us to fathom, but its about right for an unstable particle that heavy.

Remember, it is STRANGE that the typical lifetime for strange baryons like Λ0 or the Charged Σ’s can be measured in nanoseconds.

So why does the Σ0 baryon decay so quickly? OR why do we even consider it to be in the “Strange” family?

Decays

One reason to consider Σ0 “strange” is because it decays to a strange particle. Specifically, it decays, 100 percent of the time, to a Λ0:Σ0→Λ0+γ

In the process, the Σ0 throws out a photon - that is, a γ ray - which itself might be hard to explain. You see, photons carry the electromagnetic force. Photons are passed around like baseballs between particles that have an electric charge. Photons can be thought of as building blocks for electric and magnetic fields. SO what business does the uncharged Σ0 - or Λ0 for that matter - have interacting with a photon?

Electrically neutral pions, you might recall, decayed into a PAIR of photons. So perhaps it’s not weird. But π0 decays were something of an anomaly. Literally. You might recall that π0 decayed to two photons,

π0→γ+γ

because of the chiral anomaly. It involved these wild, quantum mechanical beasts known as instantons. Very nonlinear, very intricate, unusual stuff. In some sense, the neutral pion just vaporized into the electromagnetic field.

This is decidedly NOT what happens with Σ0. It doesn’t vaporize. It just decays like any other particle. So what gives?

To understand how an electrically neutral particle could spit out a photon, we have to look inside the baryon to that subnuclear goo of quarks and gluons.

Baryon Innards

The Σ baryons are all bona fide strange particles, they all have a strange quark. Σ++ had two up quarks and a strange quark. Σ− shad two down quarks and a strange quark.Can you guess what a Σ0 has?

One of each. Up, down and strange.

But wait. Wasn’t the Λ0 also made up from an up quark, a down quark and a strange quark? Well yes. And that fact explains in fact, why the Σ0 decays so quickly. It decays to the Λ0 because they both share the same number and kind of internal or valance quarks.

As it turns out, the Σ0 is something of an “Excited” version of the Λ0. Internally, you might say that the up and down quarks are buzzing around in a slightly different configuration. A configuration with slightly more energy. They’re a little more spun up, as it were. That bit of spin energy gets released by the emission of a photon, leaving that bag of quarks and gluons with lower internal energy, otherwise known as the particle Λ0.

E=mc2 after all just means that the mass is proportional to energy.

Including Photons

The internal structure of the Σ0 also explains why an electrically neutral particle can throw out a photon. It’s just electrically neutral on average. The average value of the electric charges of all the quarks is zero. But individually, they each have a charge.This brings us back to the story of the neutron. While the average electric charge of a neutral baryon is zero, the electromagnetic field need not be identically zero.

Like the neutron or the earth, the Σ0 baryon has a nonzero magnetic dipole moment. It probably should also has an electric dipole moment. All this means is that the electromagnetic fields kind of averages out to zero, but are still smeared out, in a way.

And it’s these smeared out configurations that allow the Σ0 to throw out a photon and decay to a Λ0. Or at least, that’s another fun way to think about it.