Frequently asked Questions about Elementary Particles

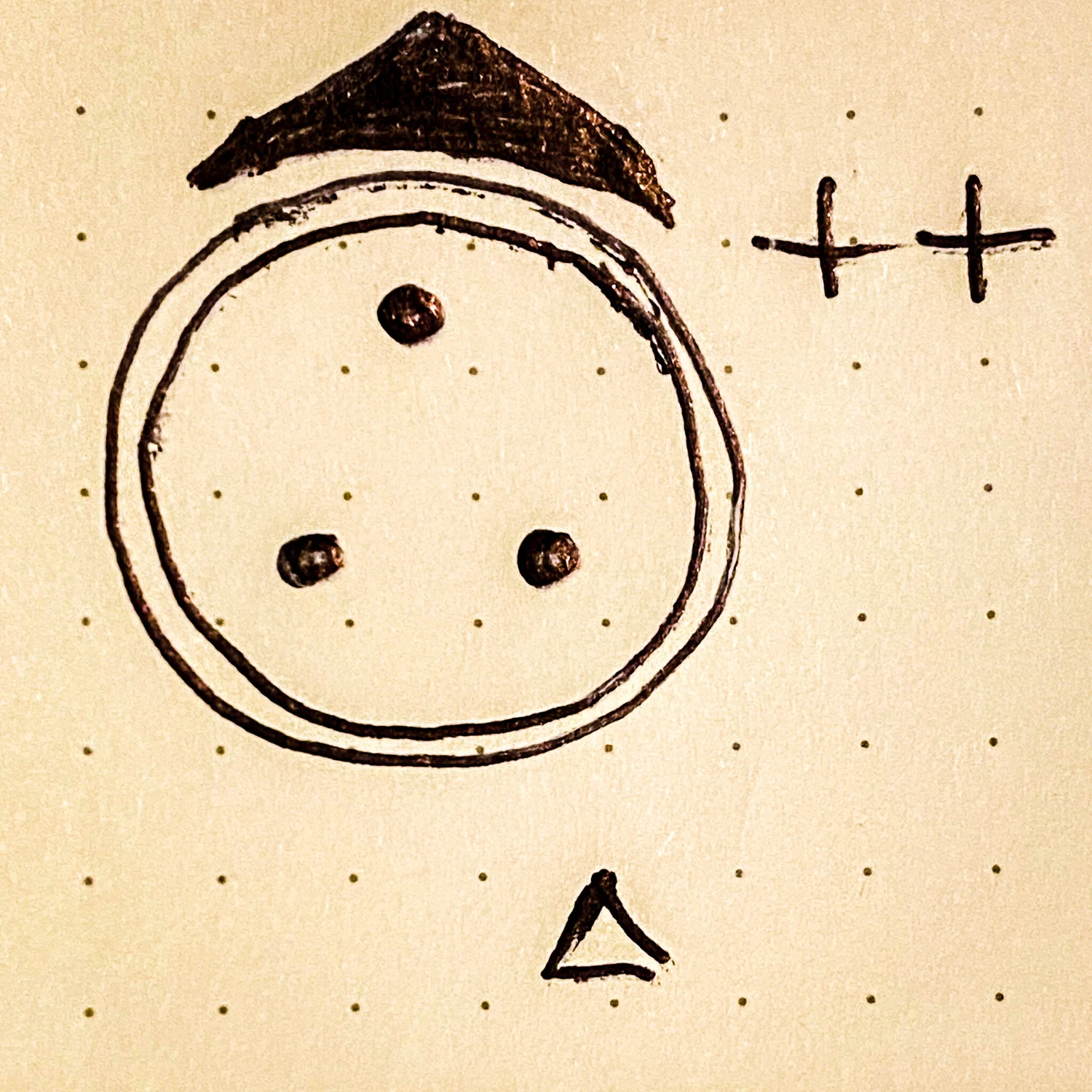

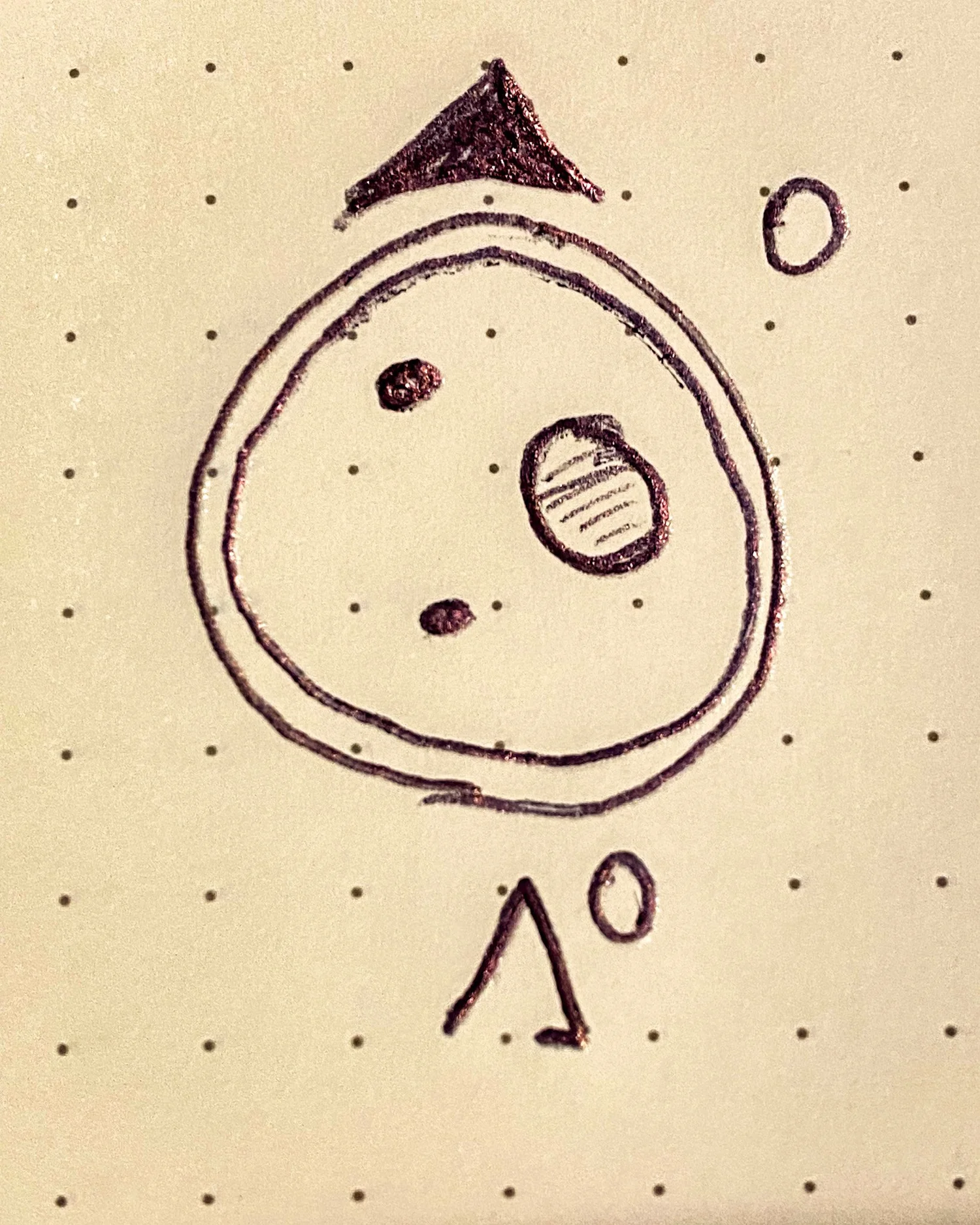

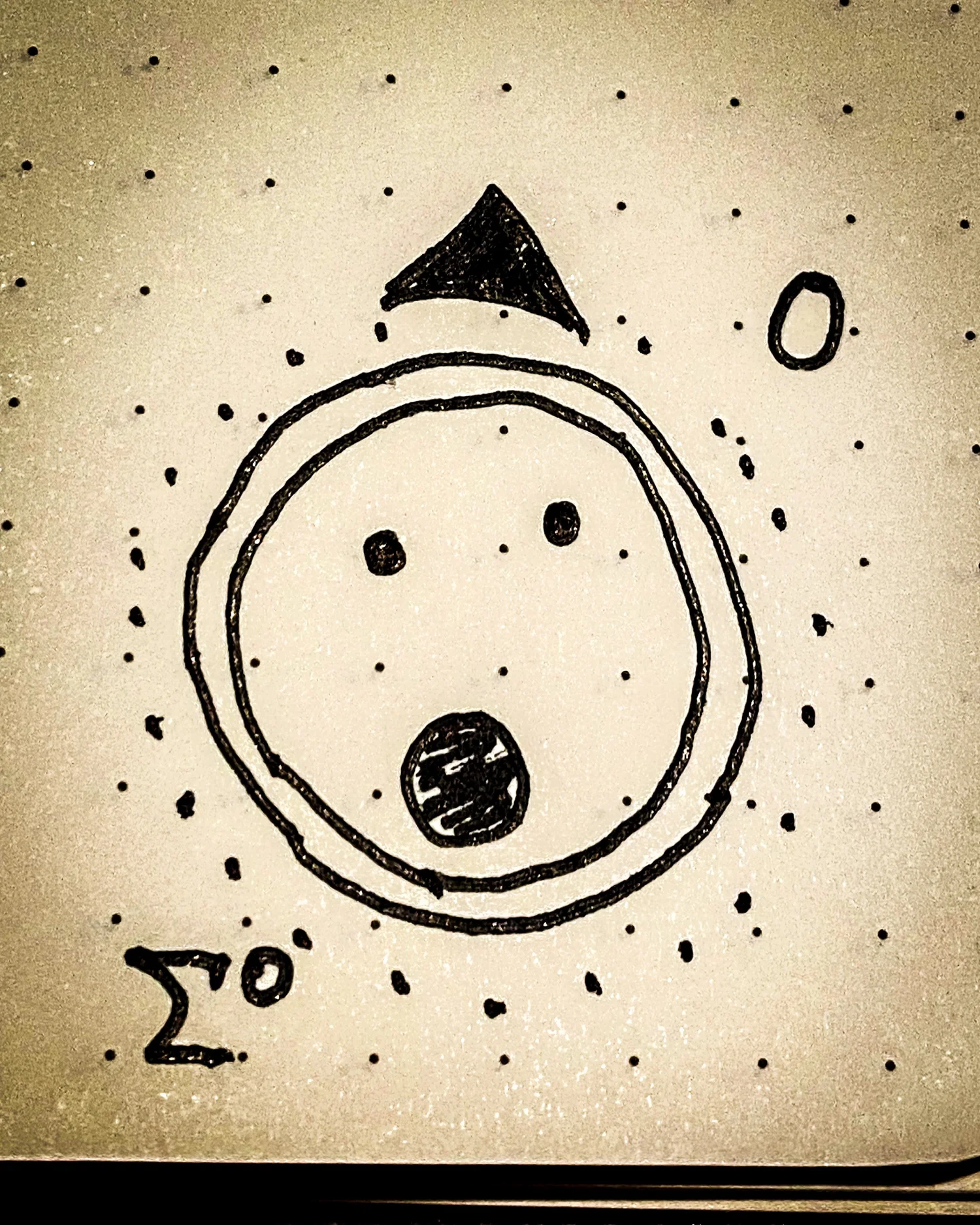

What is a particle?

A particle is a small packet of energy. It's nature's organizational scheme for energy, and energy - so far as we can tell - is never created or destroyed. But it can change forms.

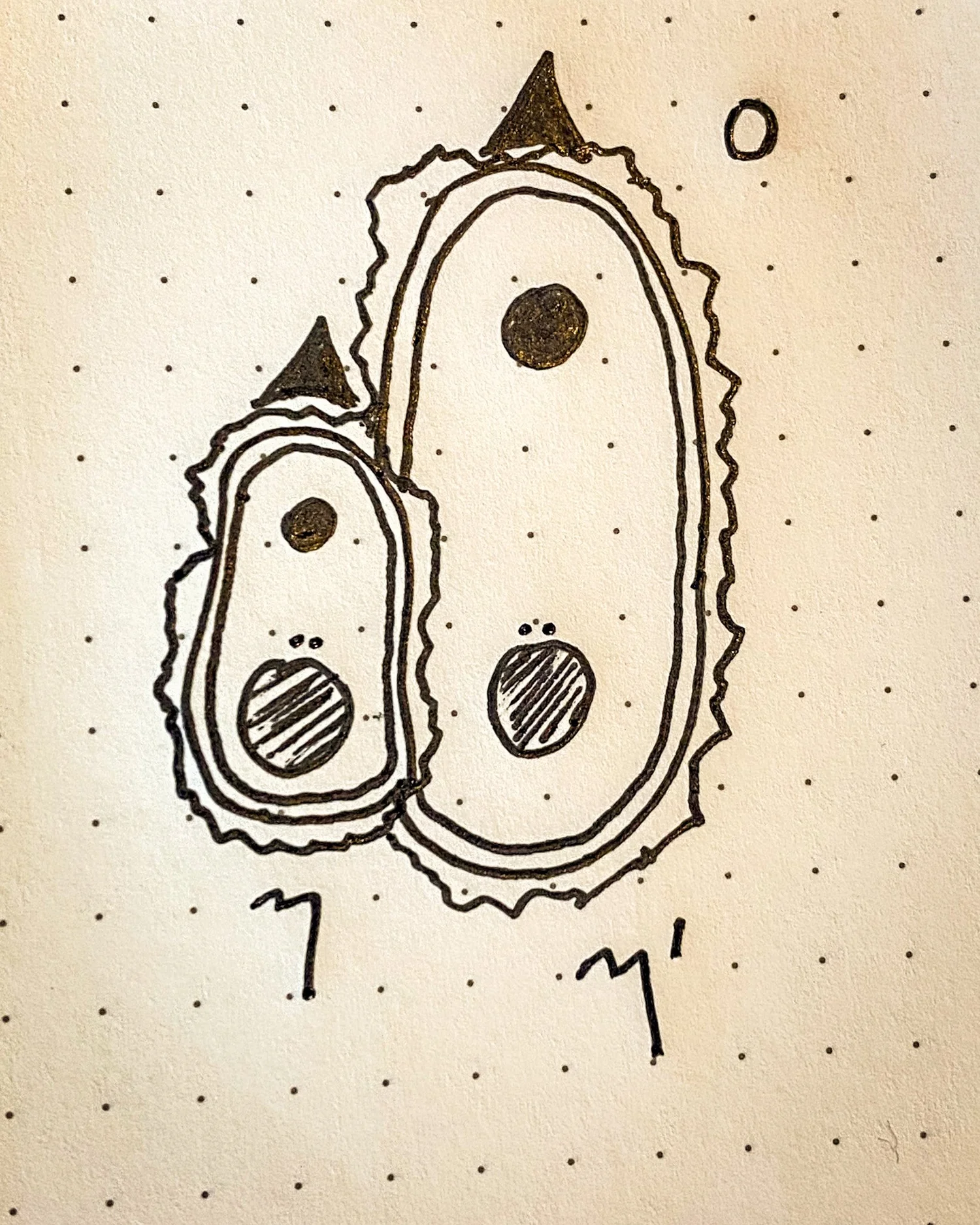

Particles can exist for a moment or for an eternity, but they don't really have a distinct existence. Unlike birds, trees or people have that their own distinct features or personalities, particles of the same species are completely indistinguishable. For example, it is physically impossible to tell one proton from another.

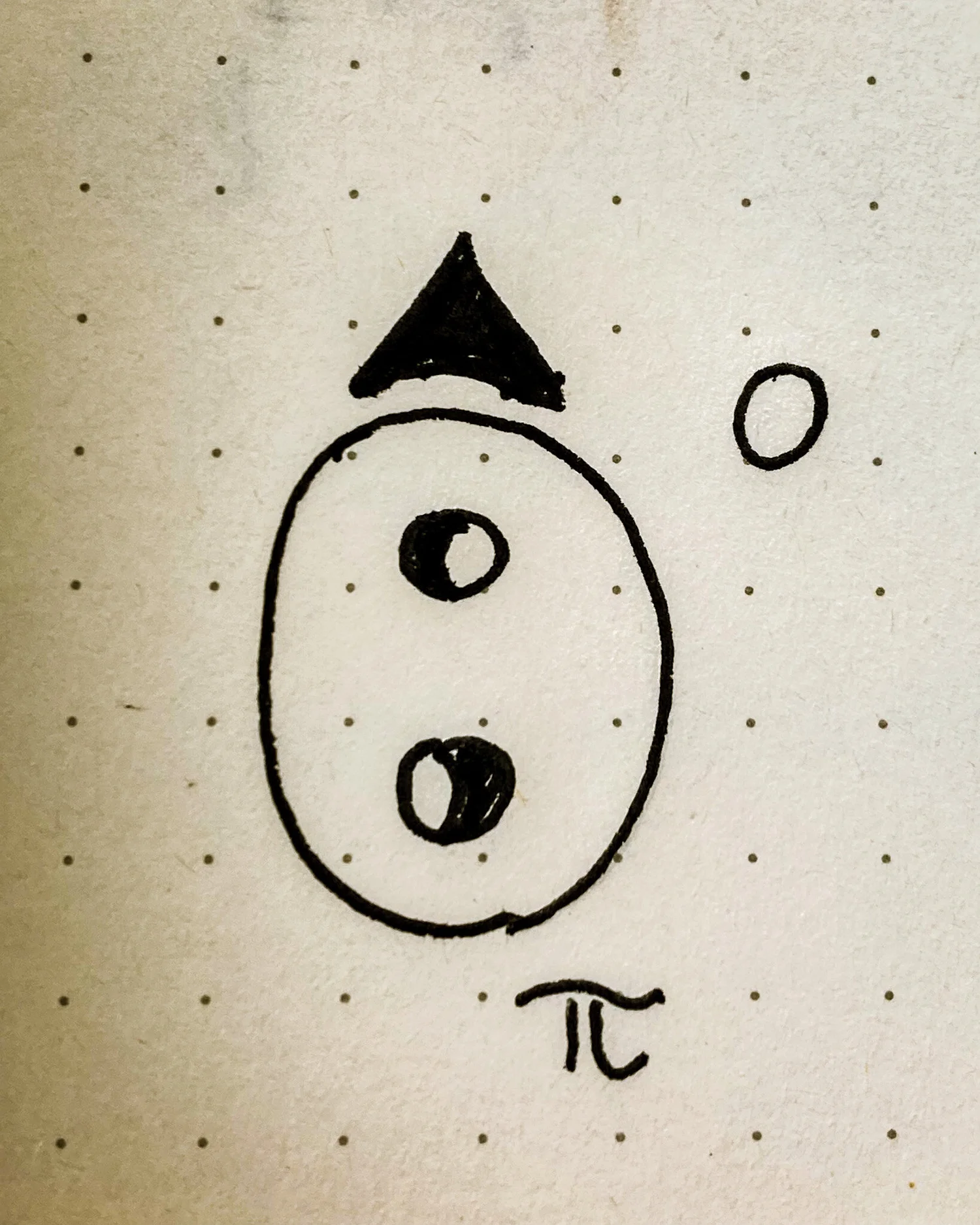

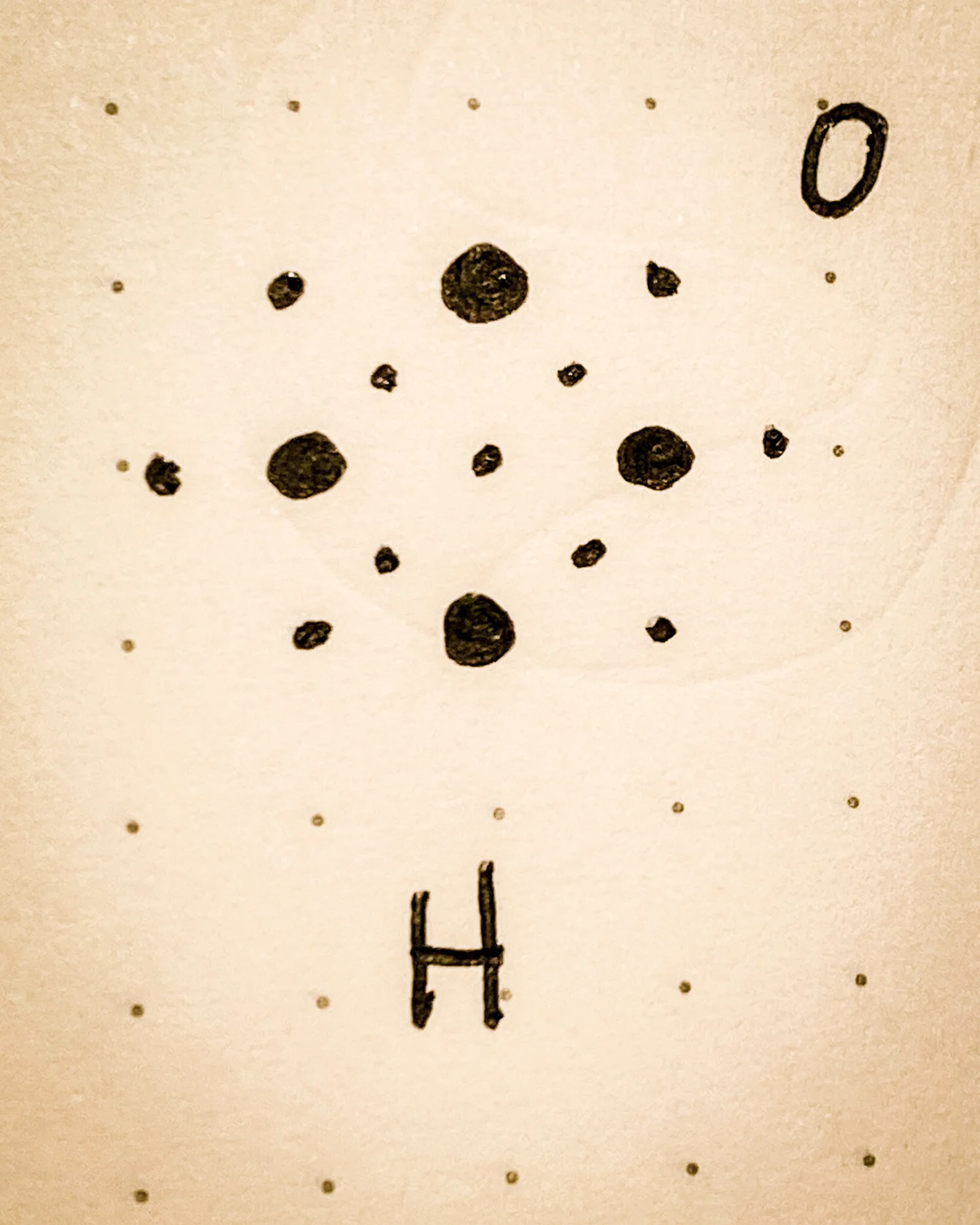

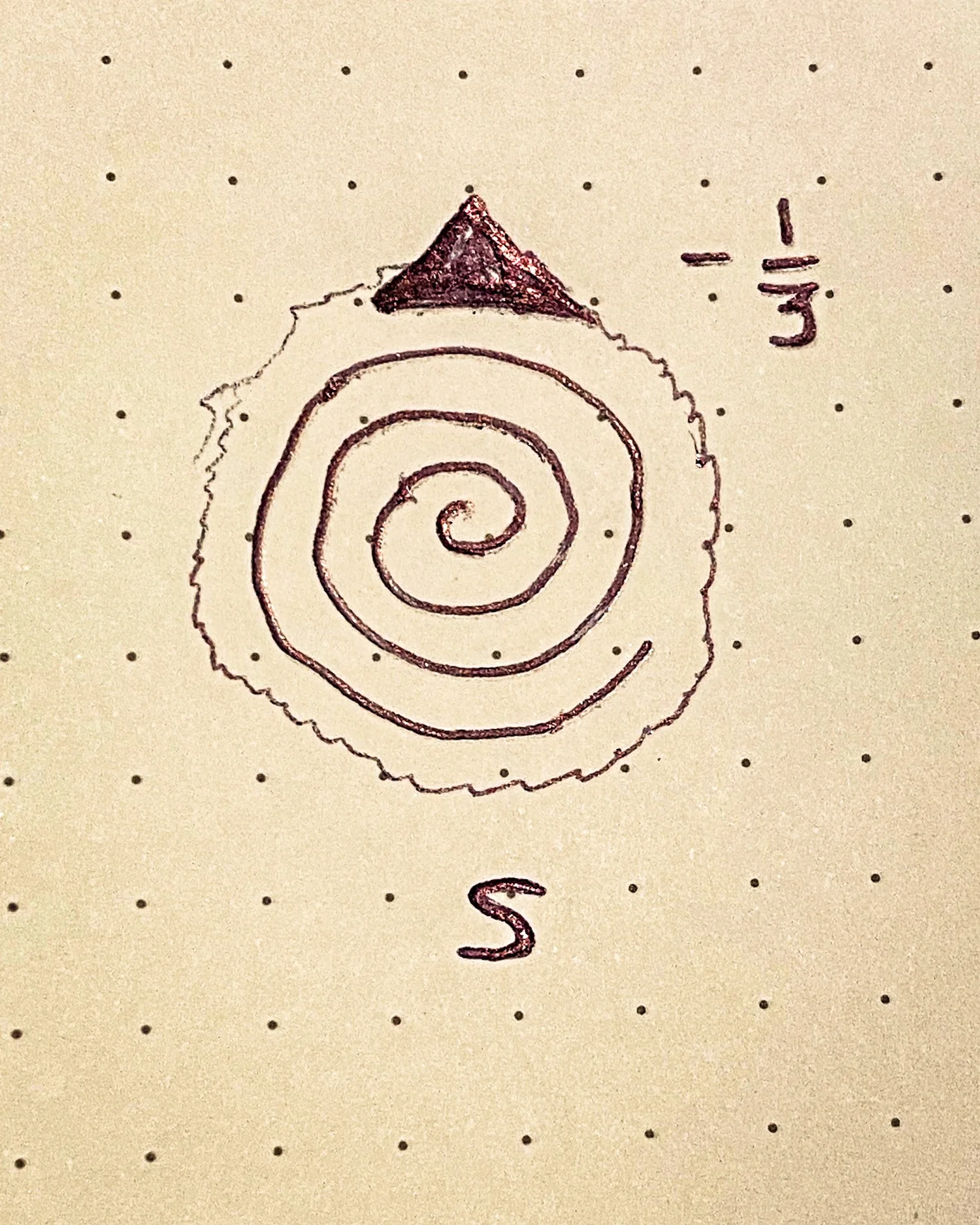

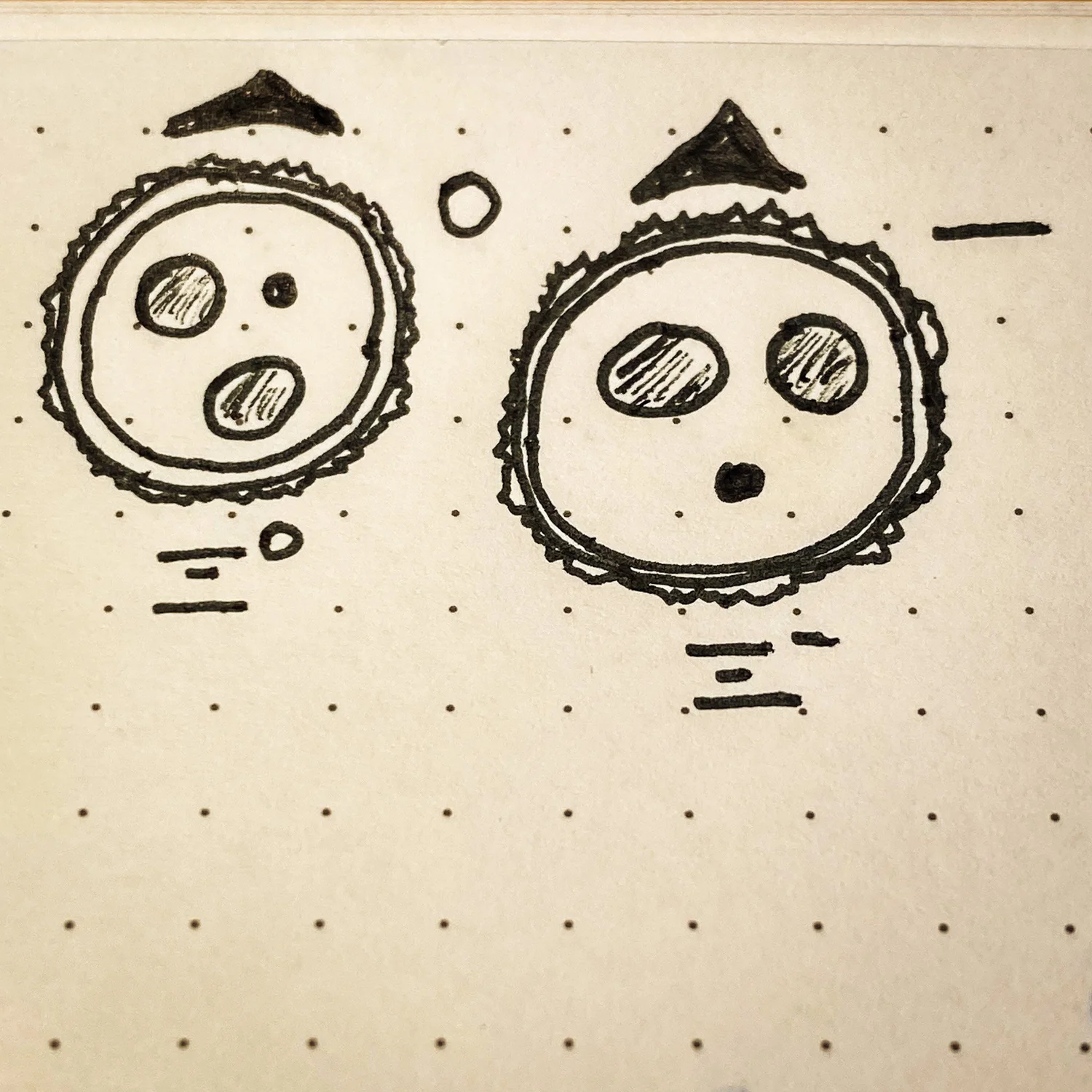

How big is a particle?

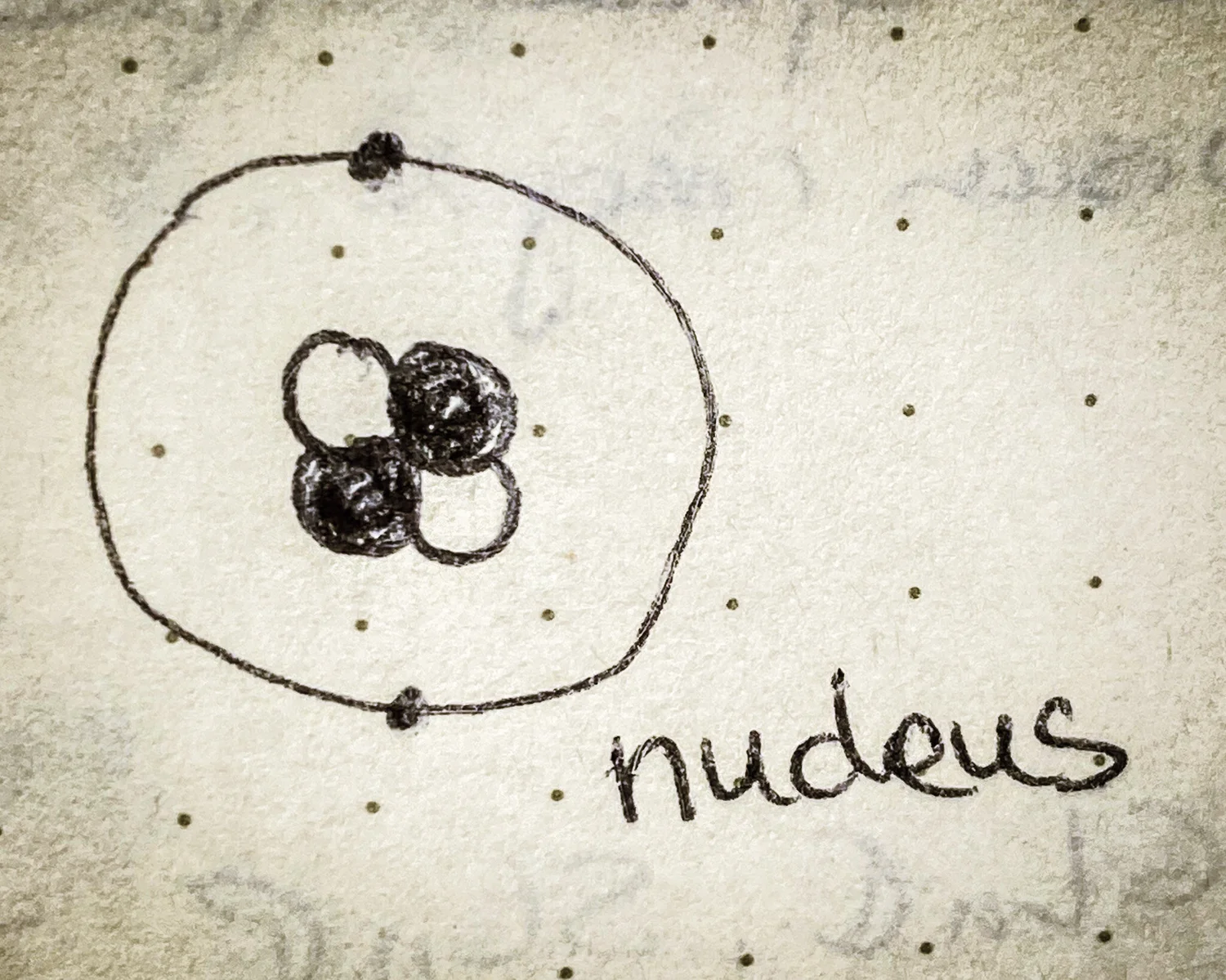

Particles may or may not have a definite size, although it's usually fine to think of them as extremely small. A particle's size is usually a determined by their inner workings, by their constituent components. For example, an atom is only as big as the size of its electrons' orbit, where as a proton is almost a million times smaller! Elementary particles, like electrons, don't appear to have any internal structure. Those particles don't even have a well-defined size!

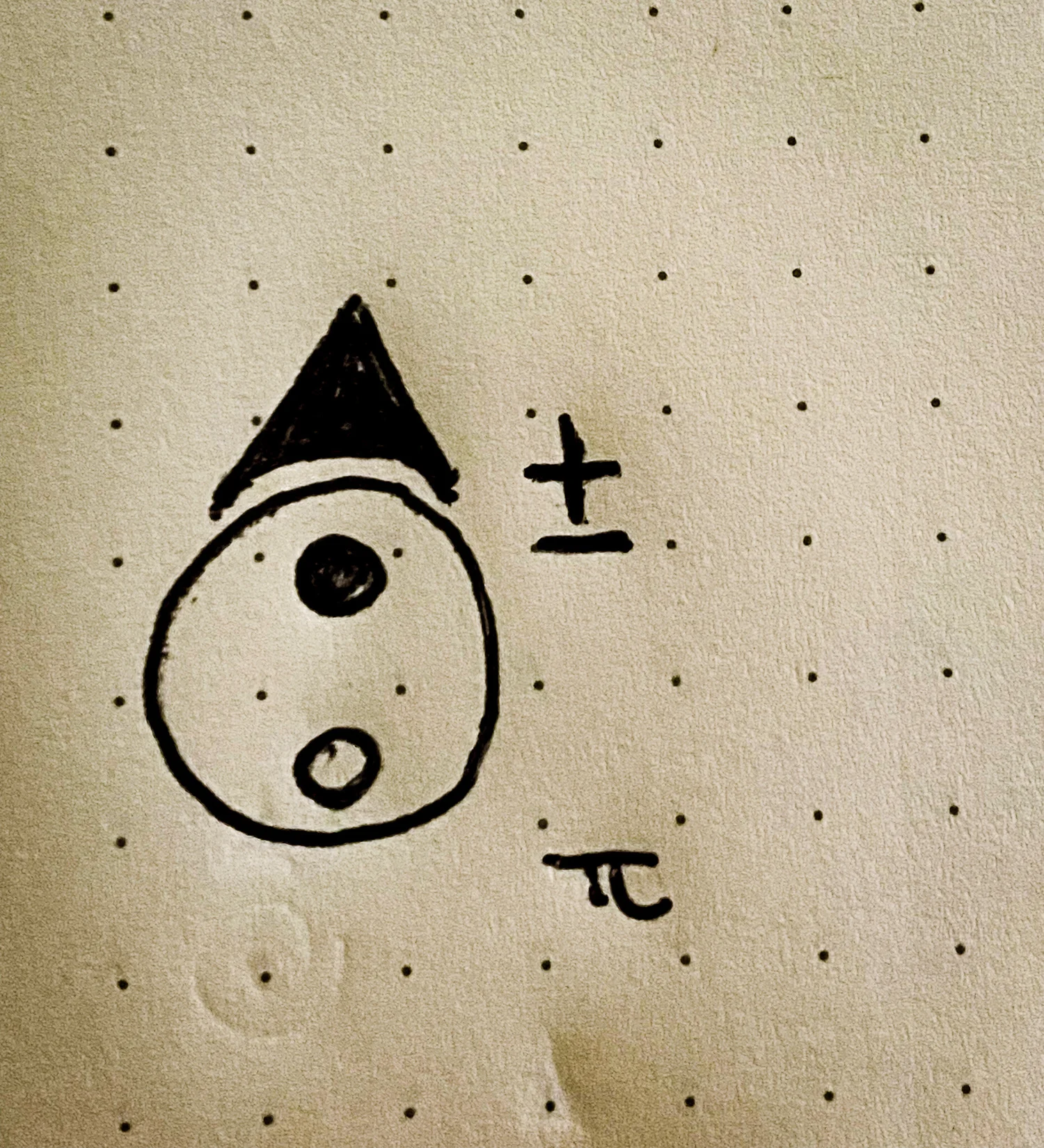

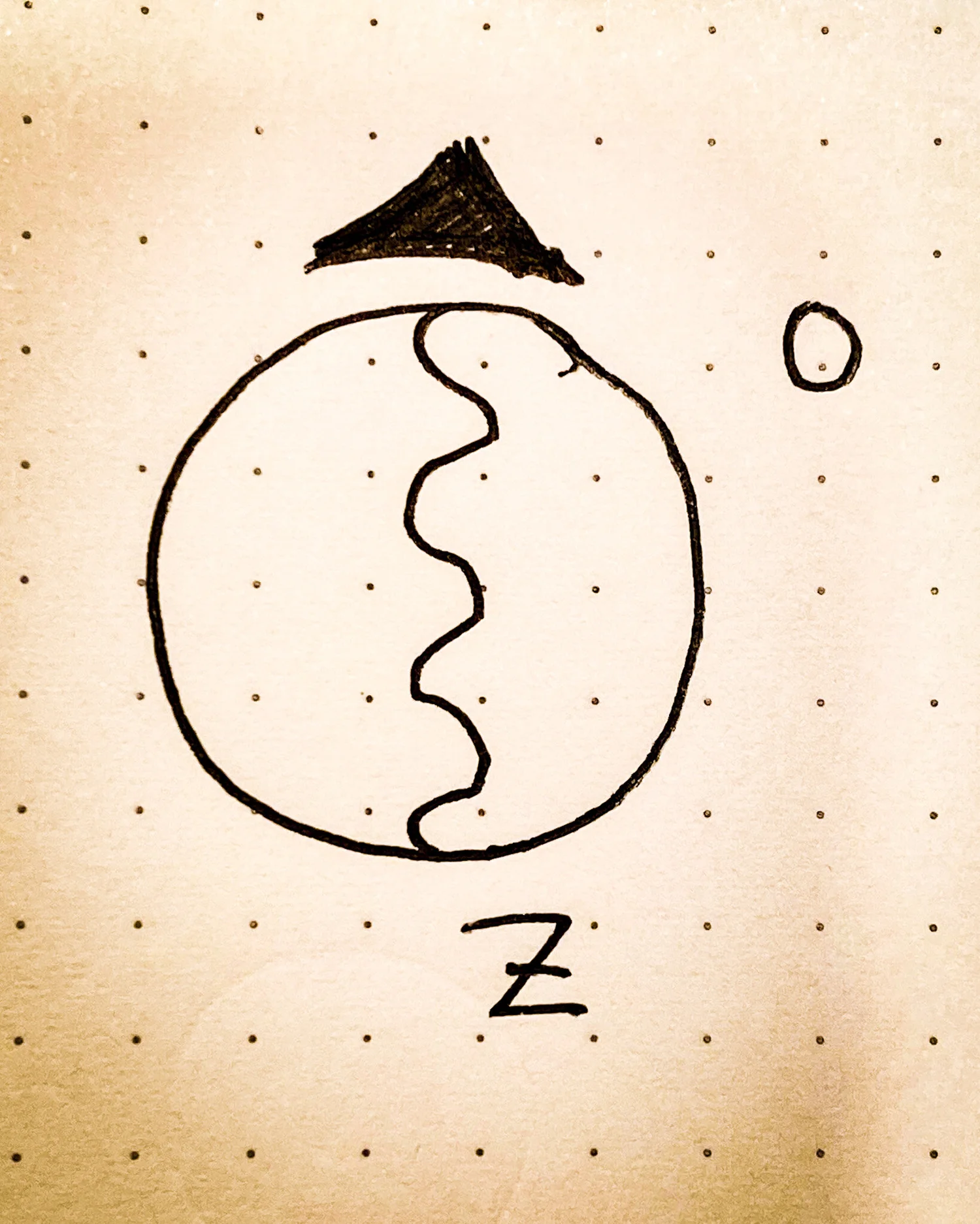

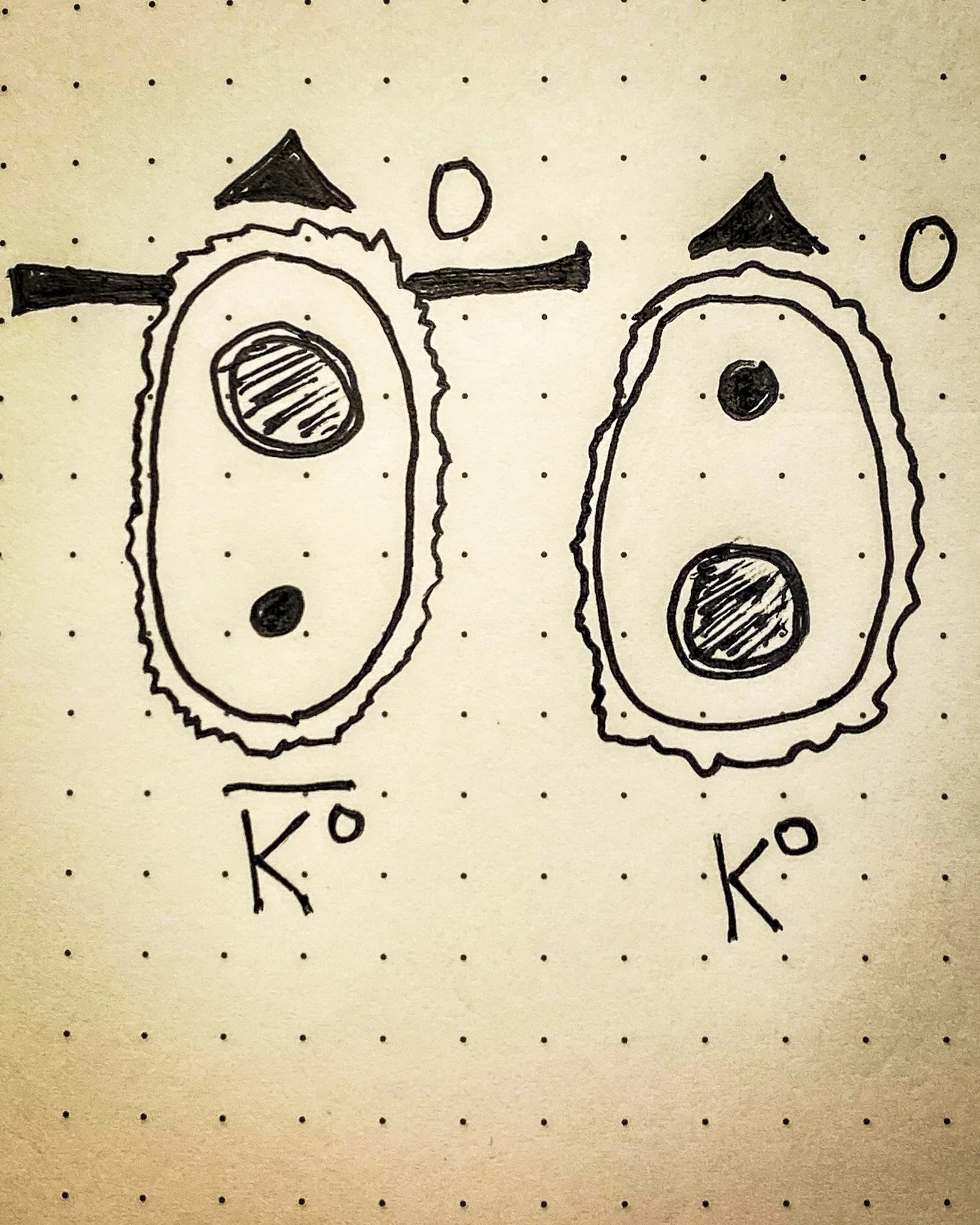

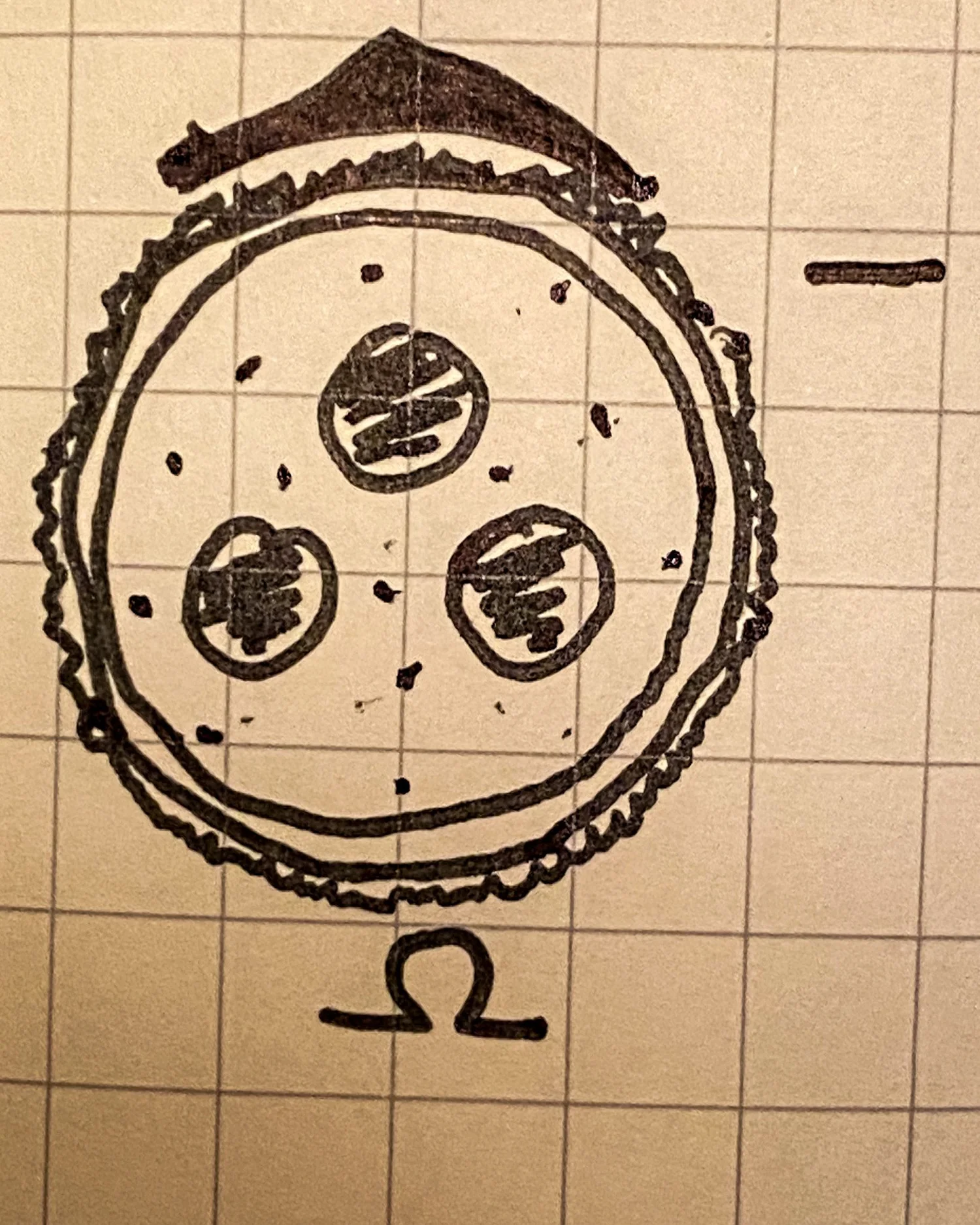

What is a charge?

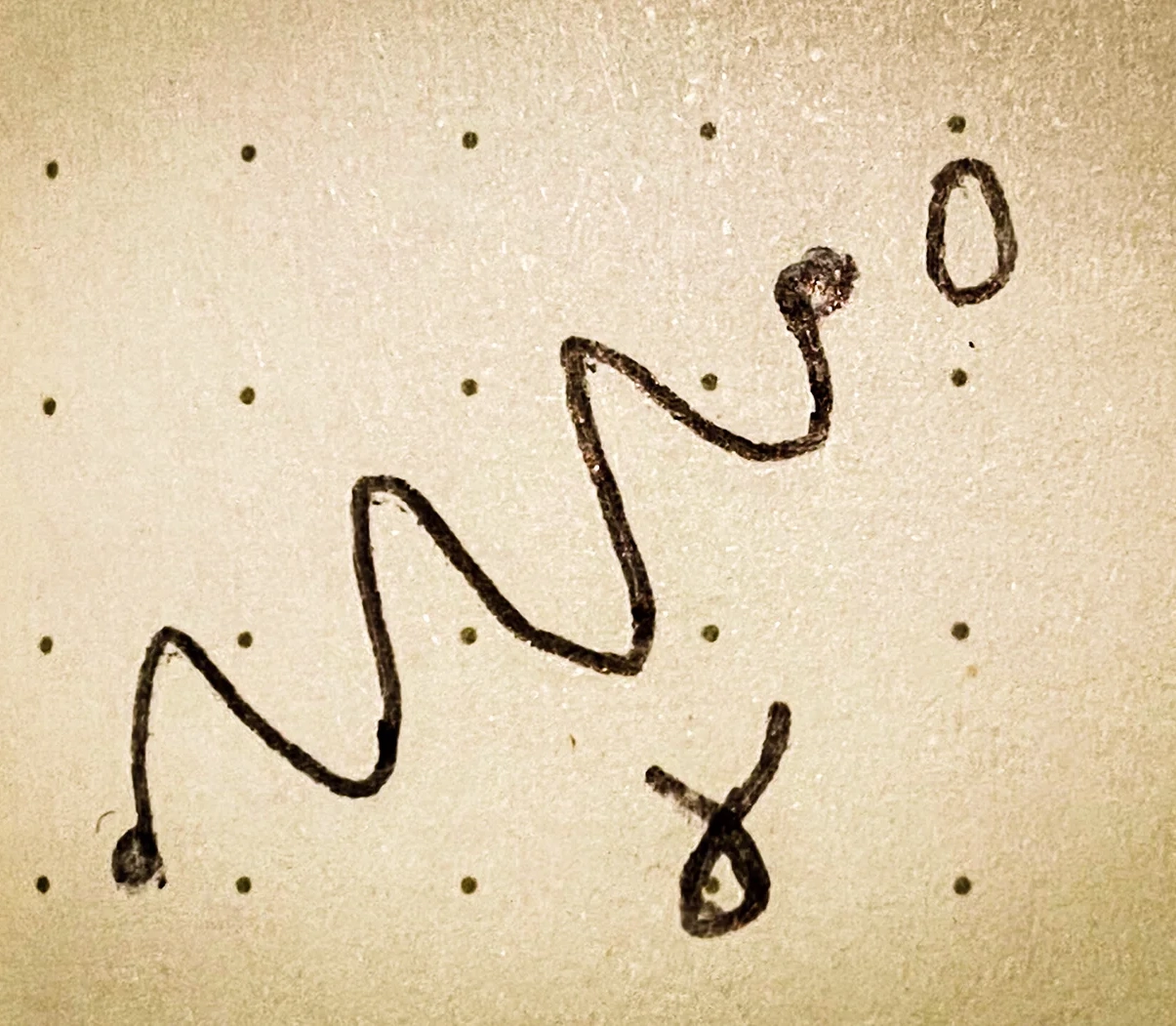

Particles are constantly pushing and pulling on each other. A particle's charge determines how strong it can push or pull. A great example is the electric charge: opposite charges attract and like charges repel. Electrons and protons have equal and opposite electric charges, which is why they attract to form atoms.

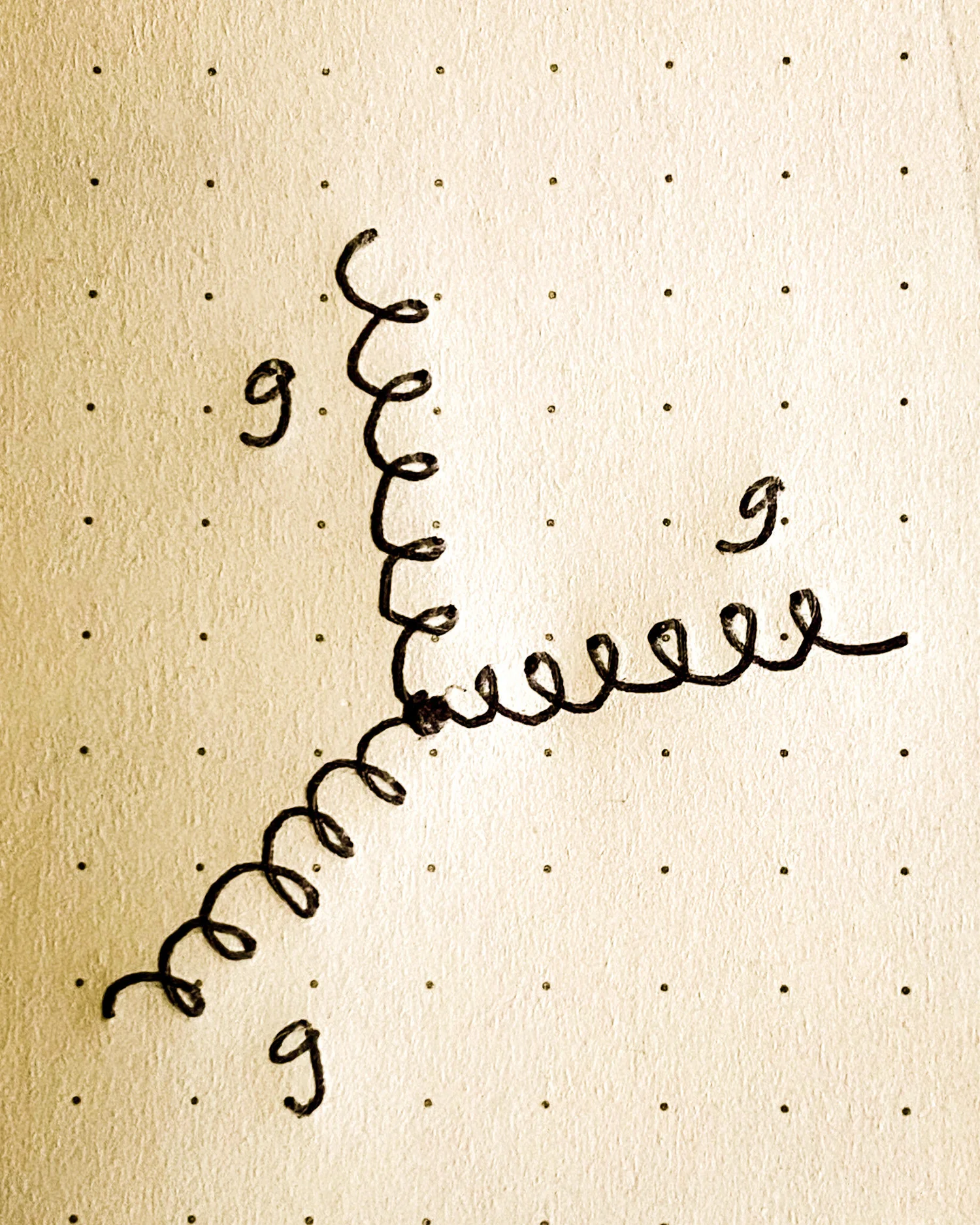

Charges are associated with the forces of nature, like the electromagnetic force. There are also the strong and weak nuclear forces, and each has its own kind of charge. In some sense, the mass is the charge for the force of gravity. Incidentally, force is just a word for another kind of particle, and we'll learn all about them in this guide.

Two particles of the same species will always have identical charges.

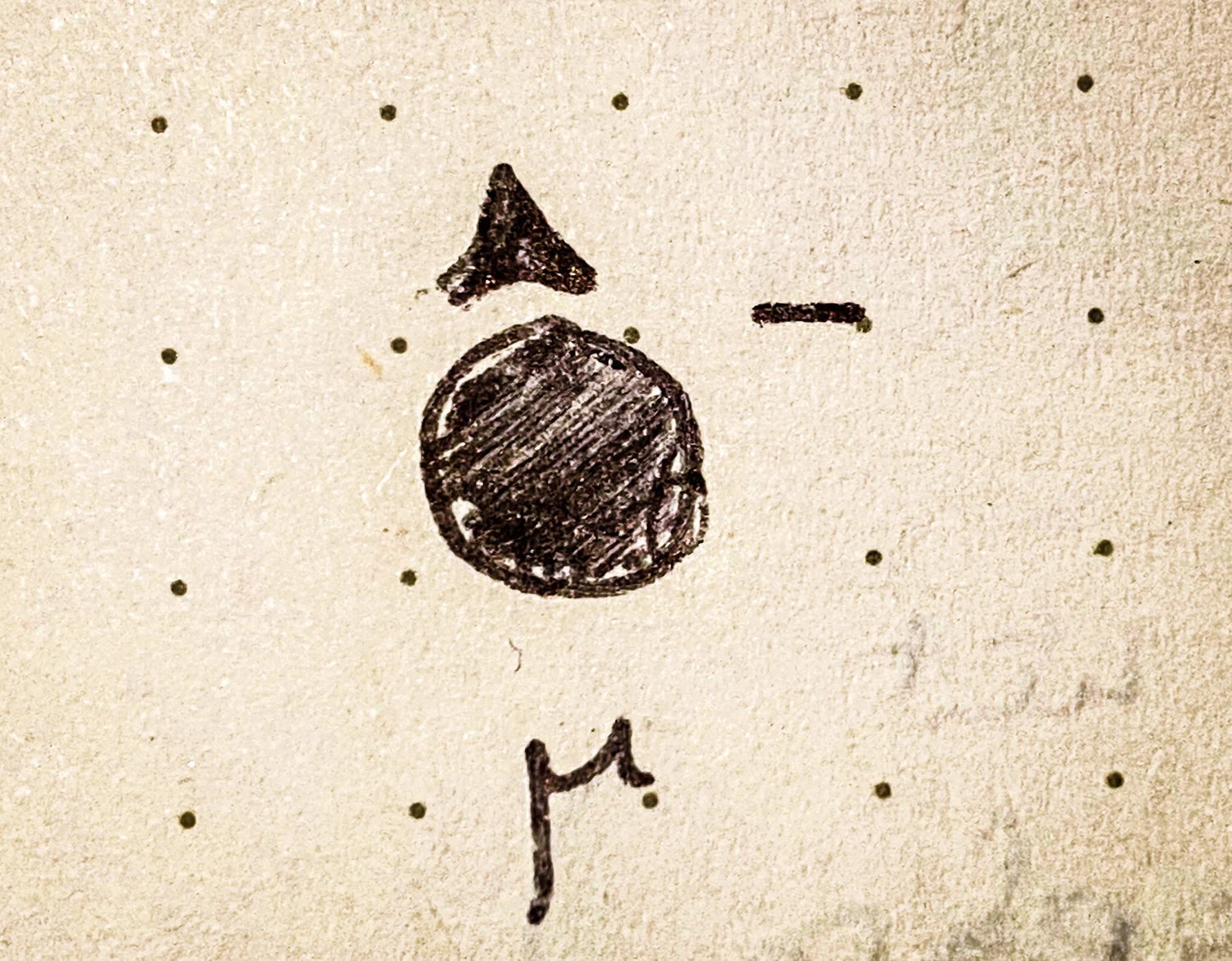

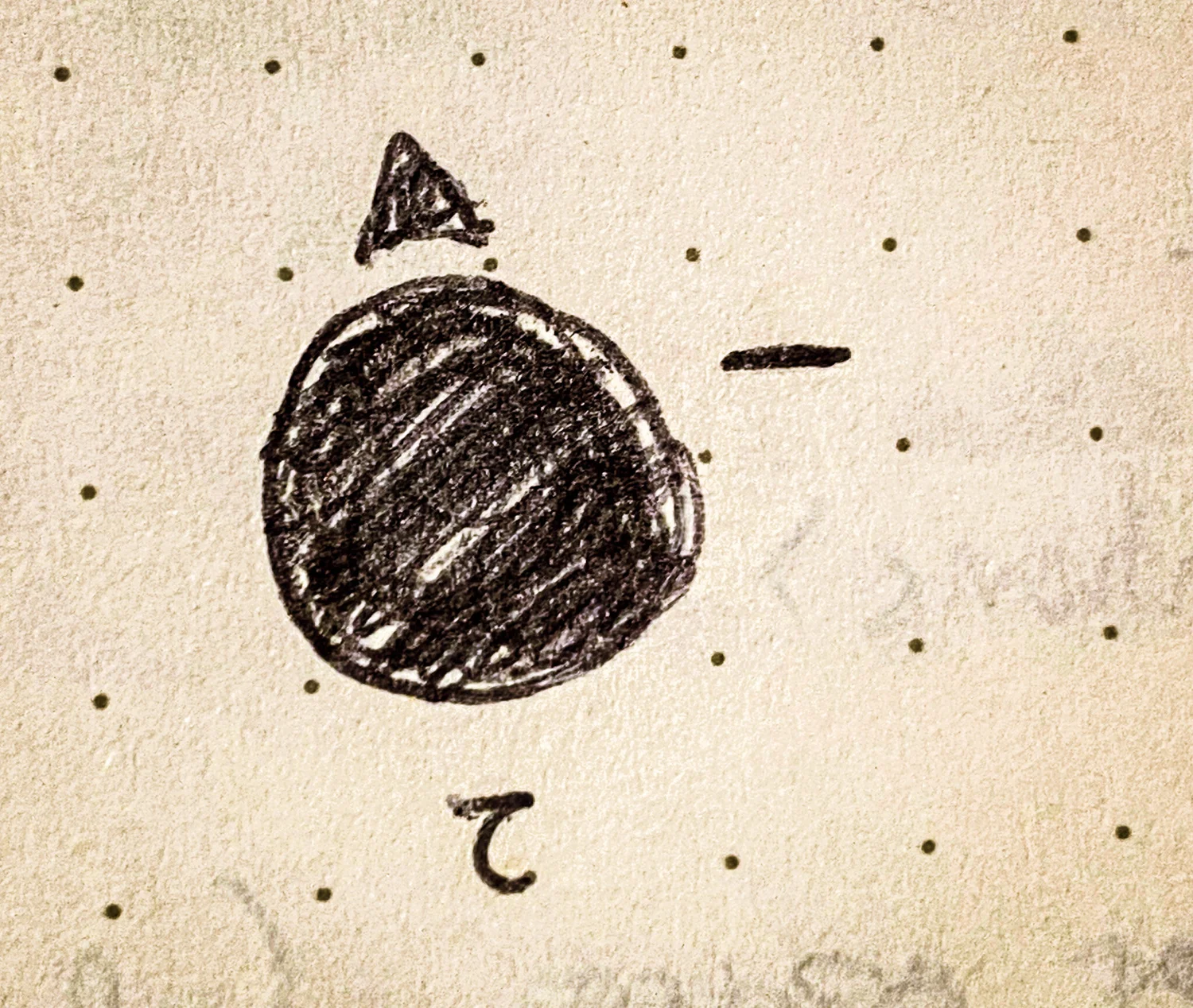

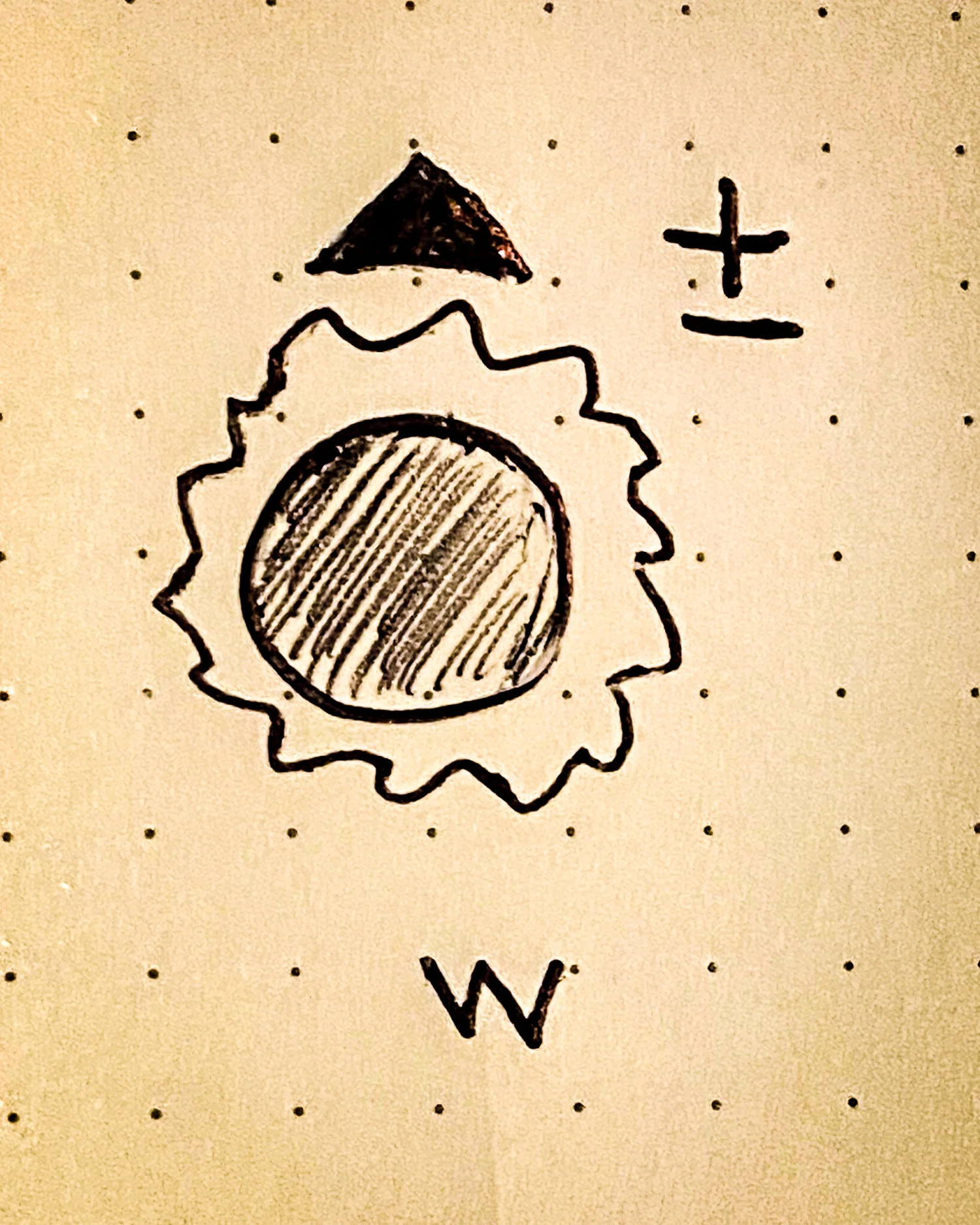

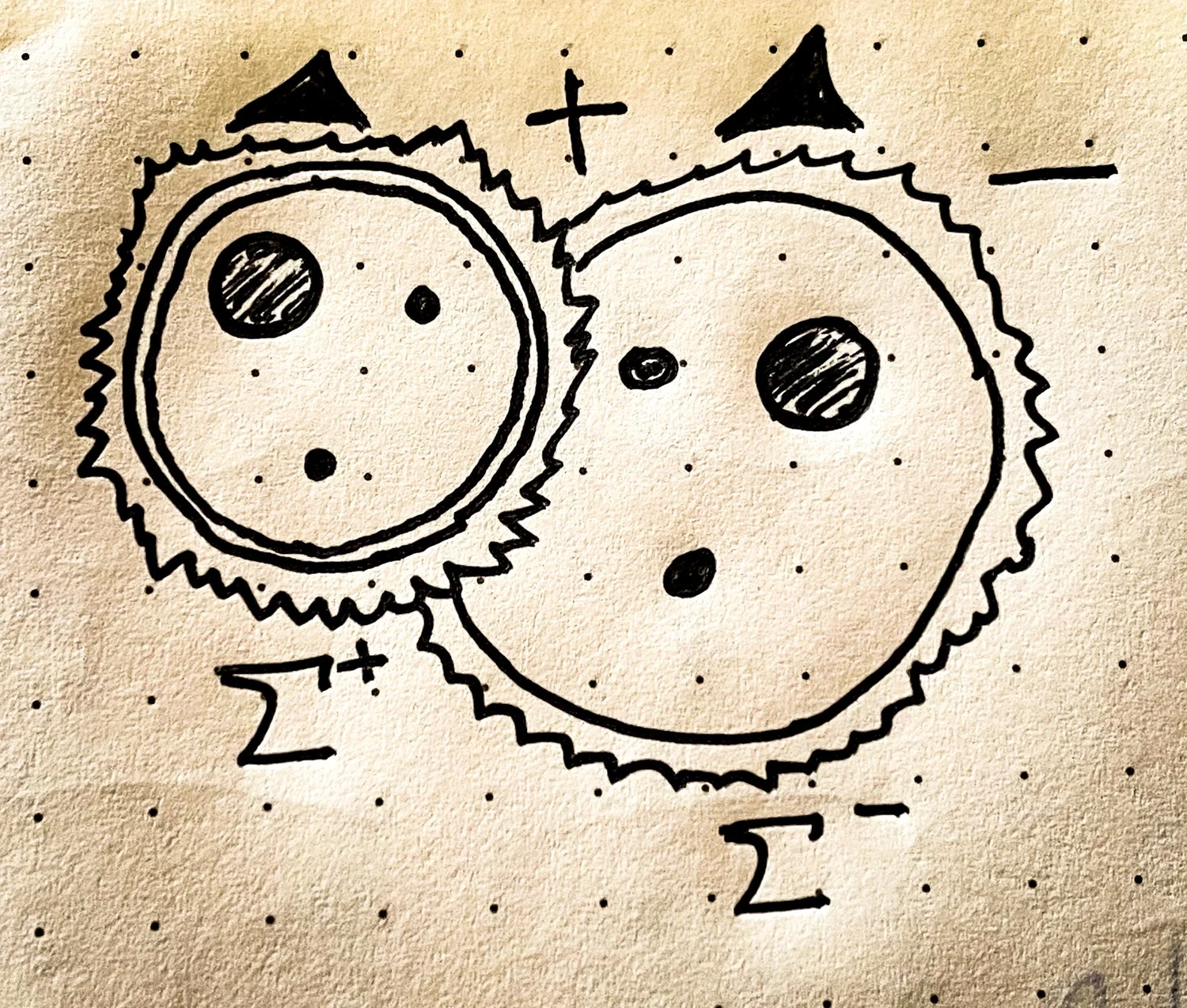

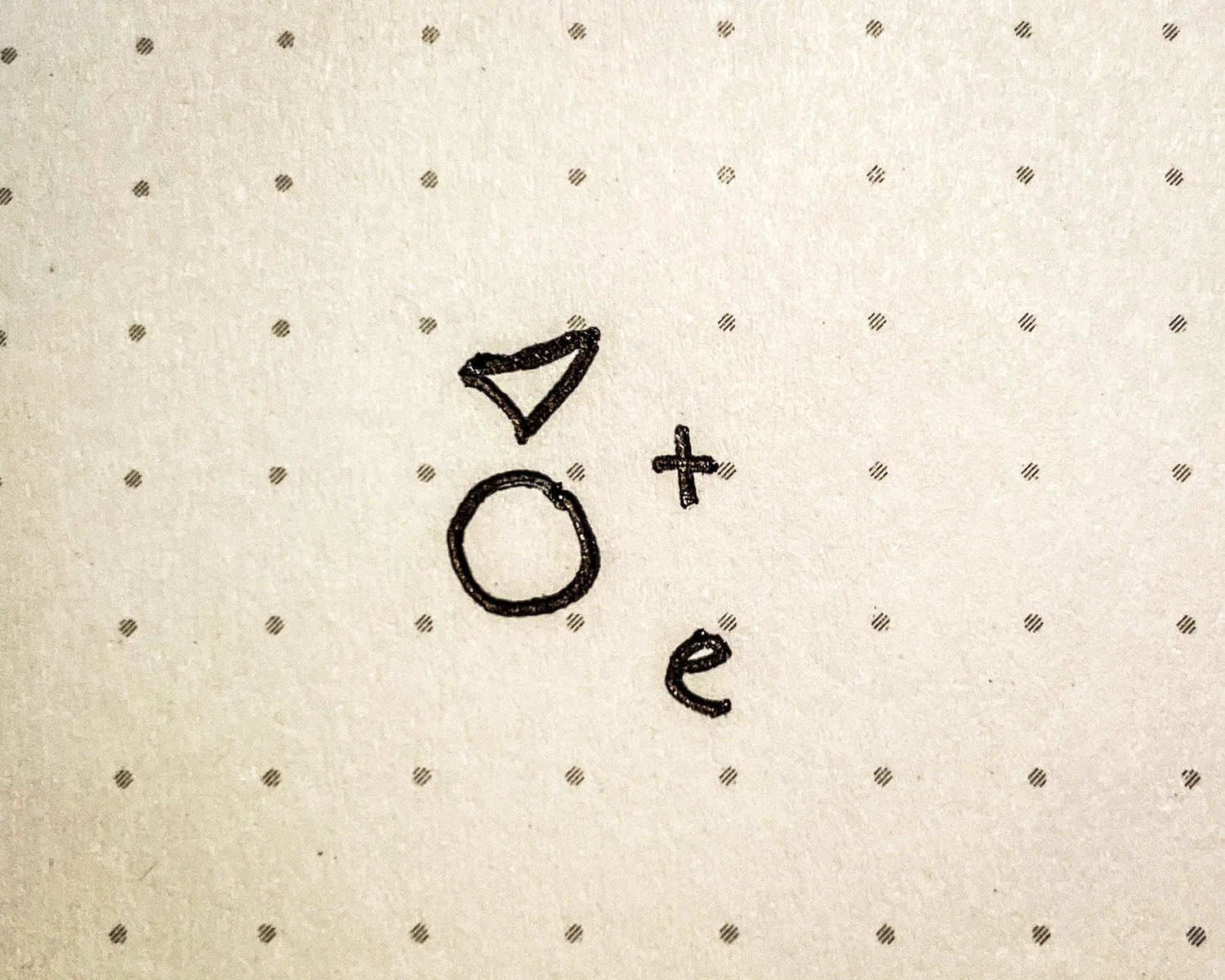

What is an MeV?

Because E = mc^2, particle physicists measure mass in units of energy. Volts are a pretty standard way to measure electrical energy. Your wall outlet has somewhere between 120 and 240 volts, which, multiplied by a particle's electric charge gives us a useful unit of energy:

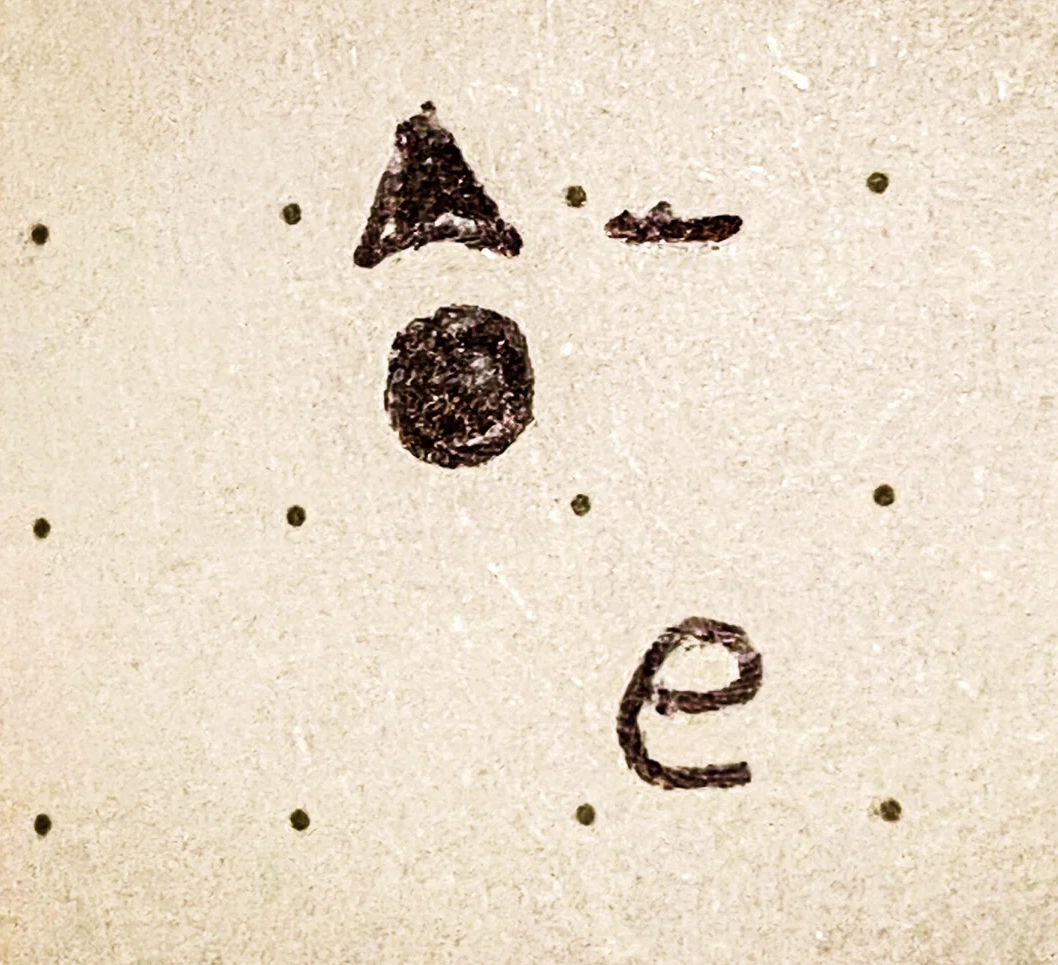

Energy = electric charge × Volts

So, roughly speaking, and electron - with charge e - comes out of your wall with hundreds of volts times the electric charge. These are electron volts, or "eV" for short.

A convenient way to measure energy in particle physics is in mega electron volts or MeV. One mega electron volt is million electron volts. Which isn't as big as it sounds. The mass energy of a hydrogen atom is about one thousand MeV.